Francis A. Schaeffer Foundation

Chemin de Jermintin 3

Chalet Les Montaux

CH - 1882 Gryon, Switzerland

www.TheSchaefferFoundation.com

udodebch@gmail.com

Dear friends, May 2015

We come to the end of the semester and will be back in Gryon when you receive this issue of “FOOTNOTES”. Let me start by saying how thankful we are that the urgent roof repair on the Foundation house in Gryon could be done and paid for thanks to the gifts we received in time before the snow. However, we do need continuing support to carry on with our work in its various aspects. If you are not yet, please consider becoming one of our supporting friends. Thank you.

Among the subjects I address in this issue of FOOTNOTES are ethical failures, including about stolen Art found in a Swiss bank; the rejection of any ideology in light of their constant attempt to destroy the individuality of persons; and the example of China’s fear of autonomous ideas. I contrast that with an appreciation of Francis Schaeffer’s intellectual home. Finally, I present a number of authors and their books which we found very stimulating. I hope you follow along.

*********

I taught my course on “Ideas (are from God) and Ideologies (are from Man)” as well as one “European 20th Century History” covering the time from WW1 to the European Union. As always, it was also a time of exposure to, and interacting with, the richness and provocations of New York. Now we return to work and live in Europe and to be with children and our ten grandchildren. I will preach in Leysin for an International Church while we host students with us for the summer after a week of teaching in Northern Norway about the Bible’s view of man, knowledge and ethics.

I will focus on ontology and epistemology as set forth in the Bible, and what difference that makes. I will contrast it with the moves in society to separate people from this unique view and leave them exposed to two extremes: strict repetitive religious/social rules on one side (total form) and the exploitation of boundless personal autonomy. The former gives us honor killings, the trafficking of women and children, the enslavement of workers in many countries and brutal policies; the latter exhibits a practices of the survival of the fittest, each person claiming their ‘rights’ and being accountable only to himself. Both extremes are justified in the name of one or the other religion.

Inhuman practices, including those we are guilty of, but rarely admit, can be justified by both extremes. The former needs the space for individuality, the latter for justice. The Bible declares to Man both personhood and freedom in a reality where law and love should flourish. Only then can there be a recognition of wrong done and repented of, to be repaired, and of ethical obligations, limits to the power we have. Not all that we can get away with, what natural or political circumstances allow, is justified.

***********

The current film “Woman in Gold” shows the struggle over the return of a Klimt painting with the same title against considerable opposition in Austria to its rightful Jewish owner (wonderfully played by Helen Mirren) It is a long battle against injustice hiding behind flimsy nationalistic and unethical arguments. Another case implicates the UBS bank in Switzerland. It held dozens of art works, worth millions from the rightful heirs of the Krainer family. After the war and their death the bank published no further searches for the Jewish heirs than a small note for three months in an official publication of the canton of Vaud.

Swiss officials discovered the $19 million estate, and, unable to find Krainer descendants despite multiple searches, claimed the windfall. Much later they settled to give $ 5.6 million of it to a foundation in Pully (not far from us in Gryon), named after Mrs. Krainer’s father Norbert Levy.

From the investment, the Foundation planned to award $8,570 last year to help three students in the canton. “I haven’t found any evidence that they’ve given any significant money to anybody,” said James Palmer, the founder of Mondex, which seeks to restore looted assets around the world. The Foundation has maintained that, under the terms of Norbert Levy’s will, it has a legal right to the assets it collected. Mrs. Kainer’s cousin, a retired economist, scoffed at such suggestions. He is “outraged” by the conduct of Swiss bank officials and the Foundation.

There are more than 100’000 Jewish art works still in un-rightful possession around the world!

***********

Ethical concerns or obligations are not raised in the life of animals and plants. They function according to a program and have no choice. Lacking freedom, they do not weigh what should be done. Human beings are different. Our minds argue over choices, the real and the imaginary, and learn from observation and memory with moral considerations and consequences. The laws in the Bible remind us of what was intended by God when we were created to be persons.

In my teaching, I lay out how human beings are distinguished from non-humans, how the brain works and what influence perception has on the growth of our understanding. I compare that with other religions and ideologies. How and where do we listen to the information we receive from the text of creation/nature, as well as from the Bible? How do we know that our understanding of the Bible is not ideological, but examined in light of what is real and true in the world, and in the opinion of fellow human beings?

Of course it goes back to our understating of the ‘imago dei’, the image of God in Man. It includes the debate over the human constitution, and there how much the theological perspective enriches the materialist, secular one. How much is that supported by recent insights in the field of neuroscience?

The consequences for life and society from different anthropologies are enormous. They provide answers concerning what human beings are for, what the purpose of our existence is, including all the questions relating to man and woman, gender and family, work and society.

***********

Speaking about ideology, I refer to John F. Burns’ article in the NYT at the end of his journalism career. In “The things I carried back” (NYT April 11, 2015) he comments on the one weighty thing he learnt while accumulating visas and passport stamps, meeting exotic datelines, returning from foreign assignments, with those Saddam Hussein puppets and Little Red Books of Mao’s wisdom, full of those richly seasoned tales of derring-do do: none of these detract from the basic question: What has he brought back?

Having spent long years in what were then and often continue to be some of the nastiest places in the world, fraudulently dressed up in their enveloping propaganda, Burns brought back an “abiding revulsion for ideology, in all its guises.

“From Soviet Russia to Mao’s China, from the Afghanistan ruled by the Taliban to the repression of apartheid-era South Africa, I learned that there is no limit to the lunacy, malice and suffering that can plague any society with a ruling ideology, and no perfidy that cannot be justified by manipulating the precepts of a Mao or a Marx, a Prophet Muhammad or a Kim Il-sung.”

Ideology produces repression by forces of the left and right, (in the guise of secular politics or spiritual religion), exhibiting man’s propensity for cruelty to man, the worst kinds of malevolence.

“My impatience with ideology has carried over in recent years to my encounters with the societies in the West that are my home: to the widespread propensity…for people who lack the excuse of brutal duress that is a constant in the totalitarian world, to fall sway to the formulaic “isms” of left and right” with “passionate intensity,” that excuse, and indeed smother, free thinking.

For, when it suits the ends of power, ideology can be invoked to prove that 2+2 = 5, or 3, or any other number that suits the state, and to demand that all embrace the madness. “It is a truly frightening thing to interview a top-ranked nuclear scientist, or a distinguished brain surgeon, or a concert pianist in China under the sway of Mao, and to hear them, though being ideological outcasts, justify with utter conviction the brutalities inflicted on them by their ideology-crazed persecutors.”

********

Ideology and its destructive effect on human existence, on the mind and creativity, on moral discourse and concerns was a theme also in Evan Osnos’ article Born Red in The New Yorker Magazine of April 6, 2015. For the Party to maintain its control over China, much human creative activity and information in areas of ideas has to be squelched. It challenges the visions and conclusions of the central authority.

Economic, commercial activity is encouraged in support of the Party’s aims, the place of China in the world, the satisfaction of the people’s desire for more goods, and the economic power of China which rises with her exports to satisfy our growing dependence on its products and availability of cheap labor.

The current effort to fight the widespread practice of corruption and to punish it among members of the Party is not simply a moral concern; corruption is untidy and makes oversight difficult, stirs up popular resentment and as a threat from within the party shows dark spots on its image. The study of why communism in Russia collapsed showed to Xi’s mind an American conspiracy, attempting to topple Communism through peaceful evolution. He is afraid of an infiltration of Western ideas of popular participation through students and teachers. He prohibits classroom materials with Western ideas and wants to seal off China, as the preservation of party power comes before preservation of law.

That is not the rule of law we admire, but the use of law in order to intimidate and to impose loyalty to party, state. China under the totalitarian claims of the Party is always unfit for multi-party democracy, as the Party seeks to suppress precisely the disruptive thinking that the country needs for the future, for continuing advances in social policy and economics, in the arts and sciences, in human moral and intellectual development. As these ideas challenge the claim of ultimate authority of the Party, Mr. Xi has limited Internet access, persecuted many secondary institutions like NGOs and Churches, and fears returning Chinese students and academics whose mind have been affected by life in a freer world.

***********

Such is the nature and weight of ideology: the dream of a perfect, unchallenged world, secure, tidy, even when it means formatting everything, including human beings. In a lecture with the response from a colleague at The King’s College I showed how straightening an insecure, fragile and untidy human experience by one or the other ideology is appealing, even at the expense of true human beings. For, being in the image of God, human beings create, live, carry out God’s mandates and thereby produce a dynamic, open history. For all people, and certainly in a world of sinners after the fall, that presents an insecure reality with an uncertainty of outcome.

Therefore ideology always attempts to abolish Man as choice-maker with a free mind, in order to avoid such insecurity and untidiness, and instead to call as ‘necessary’, ‘willed by God’, ‘in the dialectic flow of an inevitable history’ everything that happens. Women’s silence, submission, violation, forced marriage, the rule by men over them, can all be demanded by religious ideological precepts. Communism also punishes the independent mind of citizens by demanding submission to the party, the state, and assembling an obedient collective of the masses. Islam does the same, whenever it is not positively influenced by the discovery of texts by Aristotle or the belief and practices of North African Jews in the High Middle Age, or by secular, earth-bound realism today.

Ideology functions like a narrow gate which eliminates all outsiders. It is the pursuit of an imagined collective end (in some form of an ideal conformity, community, or heaven on earth), which requires for its achievement the destruction of untidy individualism, creativity, doubt and innovation.

The distinction to Jesus’ teaching about the narrow gate to God lies in the Bible’s appreciation of genuine individual diversity of persons, in new creations and in various efforts to repel the effects of sin: the Bible’s narrow gate relates to moral character and to true belief, not to personality varieties, tastes and other expressions of individual diversity. Ideologies pursue unity without diversity, while the Bible starts with an eternal unity and diversity in God himself.

Ideology is always an alien idea imposed on a more complex reality of human individuality. Therefore, any set of ideas (or propositions) needs to be exposed and adjusted to the shape of the real world. The Bible expects that, encourages that and advises that: “Come now, let us reason together” and “Always have a reason for what you believe” are direct encouragements in that direction, as is any other proposition about God and Man, history and society.

For that reason, in order to avoid submission to an ideology, it is not enough to bow to various teachings from people, pastors, or politicians and follow their instruction, unless what they advocate can be examined to be true to the real world. Personal or individual perception may require correction in light of the wisdom, learning, and reasoning of others.

Unless so examined, much Christian teaching with an appeal to blind faith is also ideological and likewise dangerous in some of the pronouncement made under its label. It is for instance ideological to teach that parents alone have a right and obligation to educate their children, that parents always know what is best for the child, or that their children should not be vaccinated. Any religion or practice, when believed and taught without the exposure to and reasonable verification in the real world becomes excessively narrow and closed off from questions of truth. Religion is then just another ideology and equally open to a multitude of conspiracy theories!

************

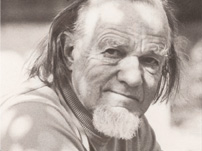

For years we have been pleased to discover many people who refer to the help and encouragement they received from Francis Schaeffer’s’ ideas in personal talks and in books. Schaeffer was – and his books continue to be – a strong influence that opened many minds to a coherent outlook on the nature of human reality. Through his ideas and insights Christians were again awakened to God’s real existence, to the truth of the Bible in all its affirmations.

In recent years we have, however, also found individuals and institutions who use a quote from, or refer to the reputation of Francis Schaeffer to bolster their current ideas or programs and thus claim a piece of the mantle. They claim his name for things and ideas that were far from his mind. He did not want to start a movement, whether theological or political, or even a series of communities. He was not an apologist, nor sought the contact with theologians.

He held conservative views where things are worth conserving, and liberal views where they do greater justice to the complexities of life in a fallen world. “If you want perfection or nothing, you will always have nothing” was a guiding principle for his outlook. There will never be perfection in any area in this life, only improvements.

What mattered to him was the Bible and the light it sheds on people, their behavior, ideas and frustrations. The treasure and fragility of human life was his concern, staying away from ideological convictions, open and responding to the changing situations in life and culture, past and present.

In a public lecture in New York on Francis Schaeffer I wanted to point out what made him such an unusual person, whose ideas gained the respect of people in- and outside his own theological identity, and many who did not expect people Bible-believing backgrounds to address issues of a philosophic, cultural and political nature.

While many details of Schaeffer’s life and views are known from his books and Colin Duriez’s good biography An Authentic Life, I wanted to shed light on the community of people and ideas that were more Schaeffer’s intellectual home, though he did not know any of them personally. This will explain much of Schaeffer’s singular perspective, attitude and approach to life. It is much more than the sum of the separate parts of Schaeffer’s life which people have in mind and select for their memory.

People who claim Schaeffer for themselves, saying how much they have been shaped by him, often have no knowledge of what shaped Schaeffer himself. They hold the remains after a Thanksgiving feast: bones, skin, the neck and lots of crumbs. They do not know the feast, fragrance and colour of the whole bird. Each person walks away with always limited, and over time changing and distorted memory, which leaves them with only separate and often distorted parts of Schaeffer to draw on in church and on political pulpits.

Schaeffer’s name is often used and misused. He had no apologetic method. He rejected presuppositionalism as the starting point, because he believed that Man, surrounded by creation, nature and human beings, is the starting point for any conversation about the truth of the universe, about God and the human condition. To avoid the creation of an ideology associated with a name, he called the study part of his work after William Farel rather than Calvin, who is identified with Calvinism.

Schaeffer’s philosophic neighbors and contemporaries were not mainly Christian, but human beings who were troubled by a puzzling, unjust, painful world of things and people, questioning how to make sense of it all. They all saw that on a host of political, social and cultural issues there are no final insights or solutions….yet. Schaeffer did not talk with Jerry Fallwell in 1970 about the start, or to rekindle and then to cruze into a conservative Christian movement. Instead he urged Christians to awaken and shape their “sleepy or absent” presence in the polis, the public square, to have their insight, voice and vote heard.

For Schaeffer Christianity is never wrapped up in the American flag or right-wing politics. He mistrusted every ideology. The lessons from history, including the history of the Church, taught him to favor a pluralistic democratic government and, while very loyal to and appreciative of America, he raised his children (and warned their future spouses) against any nationalism or exceptionalism. We are members of one human race prior to any difference in the colour of one’s passport.

In contrast to the current political concerns the central outlook of Schaeffer was not a program, an ideology and political power, but a passion to be truthful, caring and engaged to diminish the results of the fall and of wrongful thinking. Central to Schaeffer was the conviction that Christianity is only true if it is the truth of the universe: There is no other reason to believe!!

Schaeffer’s effort to give Honest answers to honest questions implies continuing inquiry, search and a desire to make sense of things, as well as a willingness to review, change, adjust and delay answers that did not meet the criteria of rationality, the facts from the external world (what we call creation) and the requirement to make life in the real world possible. From honesty, there was always a willingness to throw out the faith if it does not meet these criteria, an attitude not understood by many in his reformed synod, that ‘faith’ settles things.

“Take your time, but hurry up” was a critique of an attitude that “once you believe by the grace of God, such questions do not arise”. Hearing about an honest approach to basic questions of life drew people to his place, where they would learn and appreciate the community of people, thinking, serious about life; not primarily about faith or church, but instead about life in the market, in history, of human (“image of God”) efforts and failures enlightened by the Biblical view of the world, of Man and God.

While reviewing these aspects of Schaeffer’s practice of life, four individuals from the second half of the 20th century come to my mind, whose inquisitive pursuits concerned similar things and questions with which Schaeffer grappled. They form an intellectual fellowship, wrestling with the puzzle of life in which we find ourselves, or in which we are left behind: Left, because not everything is right yet; and left also, because unless the first questions of human curiosity are answered, there is no reason nor direction to march ahead into what might become even greater horror.

The first person is the late Irving Howe, author of World of our Fathers and A voice still heard. Howe was a man of the political Left, editor of Dissent, who saw the loss of reason in the quest for truth after the ideological fixations from the 19th century on right-wing individualism and left-wing totalitarian socialism.

Howe grieved over the loss of “Menschlichkeit”, that Jewish term requiring that we act always with decency and respect, compassion and interest as members of one suffering and persecuted people. As teacher and professor, Howe used education as tool to bring wisdom and perspective to his students, who were always more easily swayed by simple, but radical solutions at the expense of compassion, patience and delayed gratification.

Like Schaeffer, he was a radical, in the sense that “radix” means “going to the roots of things”, thinking anew when contexts change. He rejected short-lived impulse or upsurges of enthusiasm giving the momentum for people’s actions. In that he resisted apocalyptic, idealistic, authoritarian impulses, instead seeing each day in the context of ‘the past brought to life’ to make available the best of what people have thought and done in our human continuity.

Tony Judt is the second person added to that intellectual fellowship. He is not a Christian, but a truly thinking person as shown in his detailed reflections on what troubles our age after the abandonment of reason, that proud handmaiden of the Enlightenment now crippled after the rejection of Scripture. You may find out more about him in When the Facts Change; Ill fares the land; Thinking the 20th century; and The Memory Chalet.

I taught my course this semester leaning heavily on the third person of this intellectual fellowship. Bernard-Henri Levy authored The Testament of God, Left in Dark Times, American Vertigo, and Barbarism with a Human Face.

Levy is a lone voice pleading to recognize the source of all freedoms and subjectivity in our unique humanity which God’s word addresses as free agents, recognized in the existence and prodding of our conscience, over against all inevitability and determinism found everywhere from Greek tragedy, in communist ideology, in Islam, and Hegel’s view of the quasi-divinity of history, in genetics and materialism, and wherever people are assigned to a gender or racial identity. All these present an invitation to return to paganism, to nature, to the grove of trees Israel was urged to cut down as places of worship. Only in God’s testament is Man free from “thingness” to be a thinking, moral, inventive actor: child of the original Creator. He alone gives us existence and frees us from essence, from “thinghood” and mere substance into a “transcendent displacement”, torn away from old pagan localities, Babylonian gardens ((Is 1:29) and, like Abraham, from Ur of the Chaldeans to stand in conversation with God.

Levy repeats this in many forms, calling for a fundamental rejection of ‘stasis’ into a life of moral discernment, creative engagement, and significant resistance. Human beings should use their freedom in the face of fixed forms of existence, and recognize man in man, not in nature. For, the Bible understands the universe on the basis of people, in which our individuality presupposes a wresting away from mere nature, from things, from all reductionist embrace of physics, genetics and chemistry.

I have read and admired Isaiah Berlin for many years. He is my fourth person in that fellowship of thinkers. Borrowing a sentence from Kant, he wrote The Crooked Timber of Humanity and then also The Power of ideas.

Berlin explores both human greatness and the folly of much human effort to give himself meaning and direction outside of the roots that made the West what is was and still is, even though to a lesser extent. His view shows how the fascination with machines and the flight into romanticism stretch our options too far away from the core of our humanity.

All four, like Francis Schaeffer, might be called activists of the intellect who marshaled erudition and eloquence in defense of the endangered values of individual liberty and moral and political plurality. They expose the links between the ideas of the past and the social and political cataclysms of our own time: Just as the Platonic belief in absolute truth feeds the lure of authoritarianism and twentieth-century Fascism, so also does the romanticism of any period get bundled into militant--and at times even genocidal and religious--nationalism that continues to convulse the modern world.

They all discuss the importance of dissent in the history of ideas and bring to life original minds that swam against the current of their times. Ideas play a crucial social and political role--past, present and future. “Their power must not be underestimated: for many philosophical concepts nurtured in the stillness of a professor's study or the noise of a movement could and do destroy civilizations and personal lives”.

Schaeffer enjoyed much more contact with and was more interested in people who continue to address the basic questions of human beings in historical reality, resisting ideological conclusions and projects, than with theologians or people whose life revolves around going to church and holding to fixed positions. Schaeffer, like all four of these thinkers, valued doubt and inquiry as tools to go forward, appreciating the struggle of human beings to understand and work with a fractured reality, and with limited as well as sinful people. He often stated his surprise that many of his old acquaintances still repeated the same things for more than thirty years and never rethought them again. In reality life is constantly in conflict, unfinished, with new questions and unresolved situations.

His community was with people of such minds, not with church, synod or former classmates. Reality mattered to him, the real world of human existence as reflected and explained in the Bible, and explored and experienced on Roman roads and people’s lives in villages and towns, at university or in a craftsman’s shop. In such places and among such people the Bible proved to make more sense and give hope than in theological circles or even church. This is also the reason why he advocated always for a vibrant pluralistic government, for good public education, for teaching insights into the real world…and why he did not want to die: the full life of each person, truth, and the Lord’s work for the redemption of soul and body mattered above all.

I see the reason for this openness in part in connection with Schaeffer’s background in a working class family, working with hands and tools in the real world, planning to study mechanical engineering. When his 6th grade teacher read Greek myths to the class she opened his eyes to philosophic questions. They were questions that floated like so many balloons in the air.

As a 17 years old in High School he read Ovid’s Metamorphoses, because it greatly influenced so much of Western art and literature; for the same reason he also reads the Bible, the other great influence, before planning to reject it. Instead, after six months he found that the Bible not only raises the same questions, but gives him the strings of the balloons together with coherent answers about reality: “I saw that there were innumerable problems that nobody was giving answers for. But in the Bible I found answers. Even though I was finite, it put a cable in my hands which bound all the problems together and gave a systematic answer to them…In about six months”, he says, “I was flattened and impressed by the order and consistency of the Biblical system as beautiful beyond words”

For Schaeffer this was a new discovery he had made. He knew no-one who believed like he now did during 6 months, having no contact with other Christians or a church of believers.

************

During this time in NY many lectures and readings enriched us from a number of authors who introduced their new books. What a marvelous practice of bookstores to give free exposures with Q&A to authors. Two of them from Russian/Ukrainian backgrounds read from their recent books and responded to questions. Their witty and deeply touching accounts brought back many memories of my own observations in the former Soviet Union and what I have read about life under its oppressive rule. Amazingly, their colorful description were without rancor or resentment. The many absurd situations they describe deserve nothing less than critique and mockery; they are a cause for pity and sorrow for all who are still (and again) brutalized by totalitarian ideology.

Boris Fishman’s “A Replacement Life” draws on memories of his childhood in Russia before his parents’ emigration to the US and his becoming a recognized writer and author. In a semi-fictionalized style he describes various efforts and many tragicomic experiences of his older Jewish relatives. Each of them want to receive retribution payments from the German government for their generation’s suffering. The widower, whose wife died the day before her claim under the law became valid, seeks to show how he also suffered when Stalin had banished him to far-from-the-war Kazakhstan. That ‘reasoning’ leads to the temptation of using the nephew’s writer reputation and connections to submit other claims with far less justification by more relatives and their friends to draw on liberal German guilt and repayment largess until…the deception is found out.

Lev Golinkin takes us on his emigration journey as a child in “A Backpack, A Bear and Eight Crates of Vodka”. His family left Kharkov in Ukraine in the period of detente in the late 80ies, early nineties of the last century. He describes their struggles as isolated, often persecuted Jews, the chicaneries they encountered as a family, and how they were able to leave with few valuables and stuff. In the end they used the Vodka and much of their valuables as bribes to escape the ridiculous and humiliating treatments by Soviet border guards. The families make it to the US through Austria where they were hid from continuing latent Anti-Semitism towards Russian Jews.

Both authors describe the more ridiculous aspects of their experiences under Soviet totalitarianism. They use humor to mock the human cruelty of the system and the various experiences as Jews under Soviet officialdom, the minor and major insults and transgressions. I remember accounts of similar experiences in the daily lives of Russians and Ukrainians in conversations when I was invited into their homes during the six years of my lecturing teachers in seminars in the 1990s.

Another time, again at a Barnes and Noble, we listened to David Brooks, columnist of the NY Times, who presented new reflections in his columns and recent book (The Road to Character) about character building and the pursuit of what he calls ‘eulogy values’ rather than ‘resume values’: how to become the person we would like to become and be, rather than how we present ourselves, what we think of ourselves. He also expresses, perhaps better and more personal than others, the profound shift in the need for orientation, meaning and purpose, found in older generations, which then and today requires also the admission of sin to avoid the blind pursuit of success and fame in the current wide-spread moral vacuum.

The French cultural center and library Albertine on Fifth Avenue also has free public readings and discussions several times each month, followed always by a small reception. One recent event focused on Diderot’s classic “Jacques the Fatalist”, a Voltairian mockery of the church’s teaching about the will of God and divine intention behind all cruel and irrational events in history. “C’est ecrit en haut” is the repeated declaration about all things happening by divine necessity and appointment, as if history followed God’s intended choices. Were this so, it would make mockery of God’s nature and holiness, and nullify his revealed judgment over human sin and our stupid things in history which upset God’s plan. Diderot and Voltaire rejected God and church, because the church gave them the idea that God’s plan was carried out in all things. He must himself therefore bear himself the responsibility for all events.

I refer to these authors/events to let you know how much we are stimulated in mind, body and soul by so many good ideas in texts and events.

************

Warm greetings to each of you,

Udo and Deborah Middelmann